What Was Vaudeville? A Look Back at America's Variety Stage

Picture this: it's 1915, and you're settling into a plush velvet seat at your local theater. The lights dim, the curtain rises, and for the next two hours, you'll witness an incredible parade of entertainment—acrobats flipping through the air, comedians cracking jokes, singers belting out popular tunes, magicians pulling rabbits from hats, and dancers tapping their way into your heart. Welcome to vaudeville, America's most beloved form of entertainment for over half a century.

The People's Entertainment

Vaudeville wasn't just a show—it was a cultural phenomenon that defined American entertainment from the 1880s through the 1930s. At its peak, over 4,000 vaudeville theaters operated across the United States, from grand palaces in major cities to modest opera houses in small towns. Every week, millions of Americans flocked to these venues for their dose of variety entertainment.

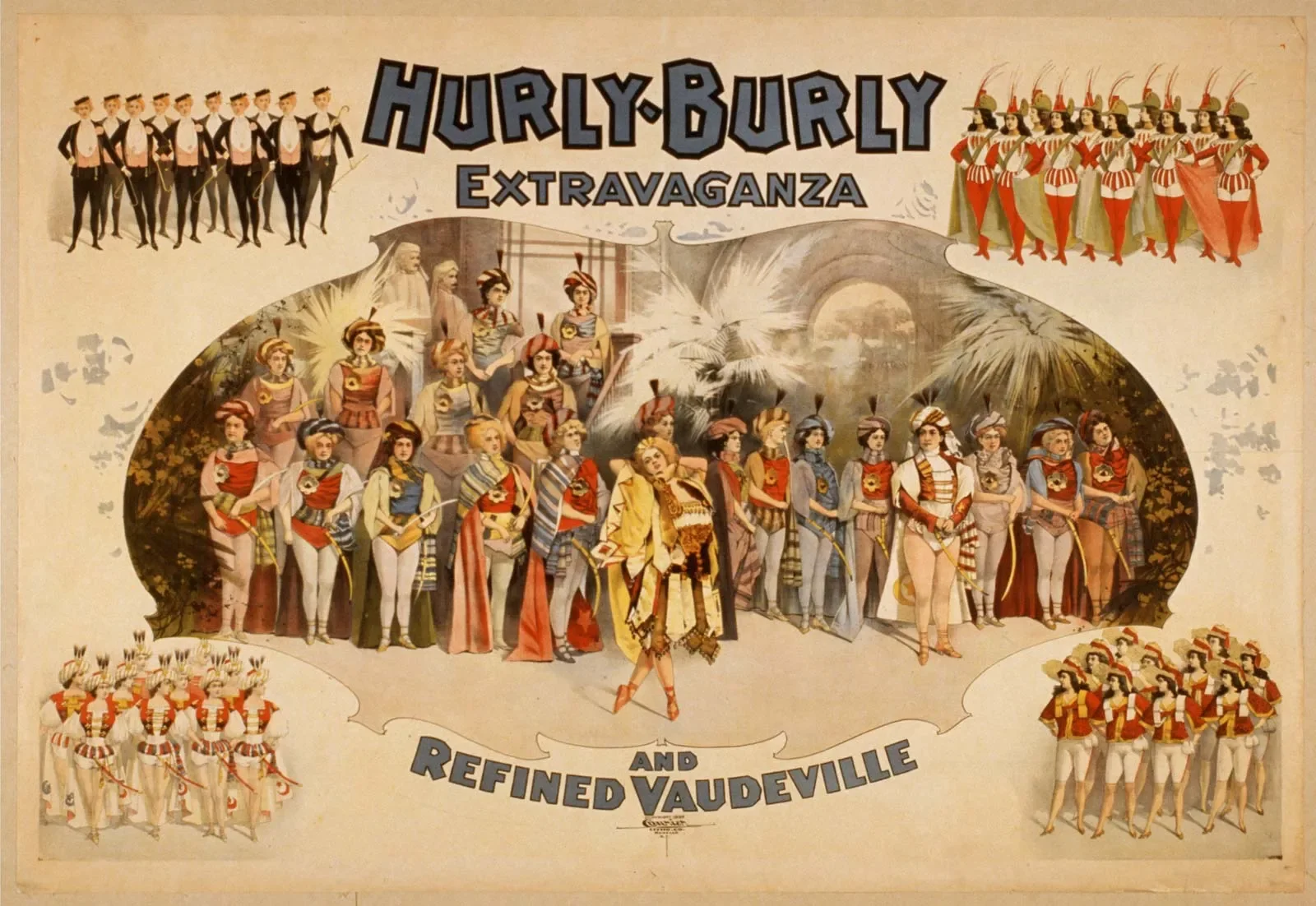

What made vaudeville special was its promise of something for everyone. Unlike the stuffy legitimate theater or the rough-and-tumble music halls, vaudeville positioned itself as clean, family-friendly entertainment. Theater owners proudly advertised "refined vaudeville" that was suitable for ladies and children—a crucial selling point in an era when many forms of entertainment were considered morally questionable.

The format was brilliantly simple: eight to twelve different acts, each performing for 10-15 minutes, creating a constantly changing kaleidoscope of entertainment. Bored by the juggler? Wait five minutes for the comedian. Not interested in the opera singer? The animal act is coming up next. This variety ensured that audiences stayed engaged throughout the entire show.

From Rags to Riches on the Vaudeville Stage

Vaudeville was America's great democratizer of talent. While society outside the theater remained deeply stratified by class, race, and ethnicity, the vaudeville stage offered unprecedented opportunities for anyone who could entertain a crowd. Immigrants fresh off the boat, small-town dreamers, and even former slaves found that if they could make people laugh, gasp, or applaud, they could make a living.

Take Harry Houdini, born Erik Weisz to Hungarian Jewish immigrants. He started as a struggling magician playing dime museums and beer halls before vaudeville transformed him into the world's most famous escape artist. Or consider Bert Williams, an African American performer who became one of vaudeville's highest-paid stars despite facing the racial prejudices of his era.

The Marx Brothers—Leonard, Adolph, Julius, Milton, and Herbert—began as "The Four Nightingales" (later "The Six Mascots" when their mother and aunt joined the act). They spent years perfecting their anarchic comedy style in vaudeville theaters across America, learning to read audiences, adapt their material, and develop the characters that would make them film legends.

These success stories weren't exceptions—they were the vaudeville dream made real. The variety stage offered a genuine path to fame and fortune for anyone willing to work hard, travel constantly, and perfect their craft night after night in front of live audiences.

The Palace Theatre: The Pinnacle of Success

Every vaudevillian had the same ultimate goal: to play the Palace Theatre in New York City. Opening in 1913, the Palace became vaudeville's unofficial headquarters, the venue where careers were made and legends were born. To "play the Palace" meant you had reached the absolute pinnacle of variety entertainment.

The Palace's reputation was built on its exclusive booking policy. Only the very best acts made it to the Palace stage, and audiences knew it. The theater became a pilgrimage site for entertainment lovers, who would travel from across the country just to see a show there.

Stars like Al Jolson, Sophie Tucker, Eddie Cantor, and W.C. Fields made the Palace their home base. These headliners commanded enormous salaries—some earning more per week than most Americans made in a year—and their names on the Palace marquee guaranteed sold-out houses.

But the Palace represented more than just commercial success. It was vaudeville's seal of approval, proof that an entertainer had mastered their craft and earned the respect of their peers. Many performers spoke of their Palace debut as the most important moment of their careers, the culmination of years of hard work and constant touring.

Life on the Circuit

The vaudeville world operated on a circuit system—chains of theaters that shared acts and coordinated bookings. The most prestigious was the Keith-Albee circuit, which controlled hundreds of theaters from coast to coast. Playing the Keith circuit meant steady work, good pay, and respectable venues.

But life on the circuit was far from glamorous. Performers lived like nomads, constantly traveling from city to city with their props, costumes, and acts packed into trunks and suitcases. They performed the same material night after night, week after week, slowly working their way up from small-town theaters to big-city venues.

The business side was ruthlessly competitive. Acts were constantly being judged, reviewed, and either promoted or demoted based on audience response. Performers developed thick skins and backup plans, knowing that a bad week or a poor review could send them tumbling down the vaudeville ladder.

Yet this constant pressure also drove innovation. Performers had to keep their acts fresh and engaging, always looking for new material, better jokes, or more impressive stunts. The vaudeville stage became a laboratory for American entertainment, where performers experimented with new forms of comedy, music, and spectacle.

The Melting Pot of Entertainment

Vaudeville reflected America's incredible diversity, showcasing performers from every ethnic background and cultural tradition. Irish comedians like Pat Rooney Sr. specialized in songs and dances from the old country. Italian performers brought opera and commedia dell'arte traditions to vaudeville stages. Jewish entertainers like Fanny Brice and Eddie Cantor drew on their immigrant experiences for both humor and pathos.

This cultural mixing created something entirely new—a distinctly American form of entertainment that borrowed from traditions around the world while creating its own unique style. Vaudeville became a place where different communities could see themselves represented on stage, even if those representations weren't always flattering or accurate.

The format also encouraged cross-cultural pollination. Performers learned from each other, borrowed successful elements from other acts, and gradually developed a shared vocabulary of American entertainment. The result was a uniquely democratic art form that helped define American popular culture.

A Typical Vaudeville Show

Walking into a vaudeville theater, you'd find your seat just as the first act took the stage—usually acrobats, trained animals, or other "dumb acts" that could perform while latecomers settled in. These opening acts served as warm-ups, getting the audience in the mood for what was to come.

The second spot typically featured a solo performer—perhaps a singer or comedian—who would begin building the evening's energy. As the show progressed, the acts got bigger and more elaborate. You might see a one-act play condensed into fifteen minutes, a demonstration of the latest dance craze, or a magician making impossible things happen before your eyes.

The next-to-closing spot was reserved for the headliner—the star whose name drew audiences to the theater. This performer got the prime position in the show, when the audience was fully warmed up but not yet tired. The evening would conclude with a spectacular finale, often featuring multiple acts or elaborate staging.

Between acts, the theater's orchestra would play popular tunes while stagehands quickly changed the scenery. The pacing was relentless—there was never a dull moment, never time for the audience's attention to wander.

The Stars Who Defined an Era

Vaudeville created America's first generation of mass-market entertainers. These weren't just performers—they were personalities who developed devoted followings and influenced popular culture far beyond the theater.

Charlie Chaplin toured American vaudeville circuits with Fred Karno's British comedy troupe, learning the physical comedy skills that would make him a film legend. Mae West shocked and delighted audiences with her bold persona and suggestive songs, pushing the boundaries of what was acceptable in "polite" entertainment.

George Burns and Gracie Allen met in vaudeville and developed their comedy partnership on variety stages. Bob Hope began as a vaudeville song-and-dance man before becoming one of America's most beloved entertainers. The Nicholas Brothers perfected their incredible tap dancing in vaudeville theaters before bringing their skills to Hollywood.

These performers didn't just entertain—they helped define what American entertainment could be. They showed that personality could be as important as talent, that connecting with audiences mattered as much as technical skill, and that entertainment could address serious themes while still being fun.

The Beginning of the End

By the 1920s, new technologies were beginning to challenge vaudeville's dominance. Radio brought entertainment directly into American homes for free. Why pay to see a variety show when you could hear similar entertainment in your living room?

The introduction of sound films dealt an even more devastating blow. Many vaudeville theaters were converted to movie houses, and the variety format was abandoned in favor of feature films. The stock market crash of 1929 and the Great Depression that followed delivered the final blow, as entertainment budgets tightened and audiences sought cheaper diversions.

The Palace Theatre, once the crown jewel of vaudeville, was converted to a movie theater in 1932. By the mid-1930s, vaudeville as a major form of entertainment was essentially dead, surviving only in small venues and radio variety shows.

The Legacy Lives On

Though vaudeville disappeared as a distinct entertainment form, its influence shaped everything that followed. Television variety shows like "The Ed Sullivan Show" and "Saturday Night Live" followed the basic vaudeville template of mixing different types of acts in a single presentation.

The performing techniques perfected in vaudeville—precise timing, broad physical comedy, direct audience address, and the ability to adapt material to different crowds—became the foundation of American entertainment. Every stand-up comedian, talk show host, and variety performer owes a debt to the skills developed on vaudeville stages.

Perhaps most importantly, vaudeville established the idea that entertainment should be democratic and accessible. It proved that audiences hungered for variety, that different types of acts could coexist successfully, and that entertainment at its best brings people together in shared laughter and wonder.

America's Great Training Ground

Looking back, vaudeville served as America's unofficial entertainment university. It was where performers learned their craft, developed their personas, and discovered what worked with audiences. The constant performing, traveling, and adapting required by vaudeville life created entertainers who could handle any situation, read any crowd, and deliver under pressure.

The vaudeville experience taught performers to be professional, reliable, and versatile. They learned to work with minimal rehearsal time, adapt to different venues and audiences, and always be ready with backup material if something went wrong. These skills proved invaluable as entertainment moved into radio, film, and television.

Today, as we swipe through endless entertainment options on our phones and tablets, we might recognize something familiar in vaudeville's approach. The same desire for variety, the same appetite for bite-sized entertainment, and the same hope of discovering something new and delightful drive our modern entertainment consumption.

Vaudeville may be gone, but its spirit lives on wherever entertainers seek to capture audiences with skill, personality, and that magical connection between performer and crowd. It reminds us that great entertainment doesn't just pass the time—it creates shared experiences that bring people together and make life a little brighter.

The next time you attend a variety show, watch a comedy special, or even scroll through entertaining videos online, tip your hat to vaudeville—the uniquely American art form that proved that when it comes to entertainment, there's nothing quite like a good show.